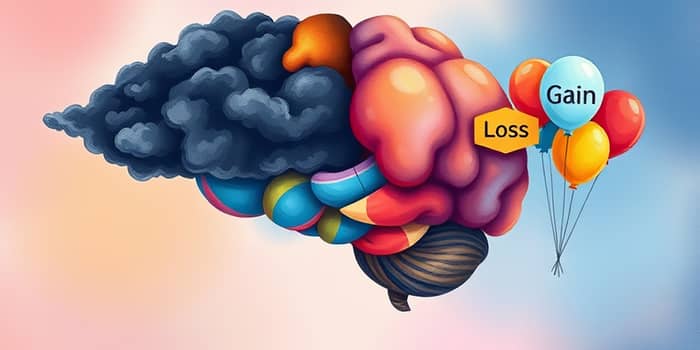

Imagine losing $100 from your wallet; the sinking feeling is visceral and immediate.

Now, think of finding $100 on the street; the joy is real, but often less intense.

This disparity captures the core of loss aversion, a cognitive bias where losses loom larger than gains.

It explains why we cling to what we have and fear change, even when opportunity knocks.

Understanding this bias can transform how we make decisions in finance, relationships, and daily life.

Loss aversion is rooted in how our minds evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point.

Prospect theory, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, formalizes this with an S-shaped value function that shows steeper curves for losses.

This means the pain of losing $50 feels roughly twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining $50.

Such insights challenge traditional economic models that assume rational decision-making.

By recognizing this bias, we can start to question our instincts and strive for more balanced choices.

Kahneman and Tversky's work in the late 1970s revolutionized behavioral economics.

They introduced loss aversion as central to human psychology, arguing it stems from evolutionary survival pressures.

Key experiments illustrate this bias vividly:

These examples highlight the emotional weight of losses that skews our risk assessments.

Understanding these experiments helps us see loss aversion in action, from small daily decisions to major life changes.

This bias influences everything from investing to personal habits, often leading to suboptimal outcomes.

For instance, in finance, people tend to hold onto losing stocks too long, hoping to avoid realizing a loss.

Similarly, in relationships, the fear of breakup can prevent us from pursuing new connections, even when unhappy.

Key behavioral impacts include:

In daily life, this manifests as hesitation to switch jobs or adopt new technologies, driven by the fear of what might be lost.

By acknowledging these patterns, we can actively work to counteract them and embrace growth opportunities.

Modern science provides compelling evidence for loss aversion through brain imaging and physiological responses.

Studies show that the amygdala, involved in emotional processing, activates more strongly during losses than gains.

Autonomic responses, such as increased heart rate and pupil dilation, are more pronounced after losses, indicating deeper emotional impact.

This neural wiring likely evolved from survival instincts, where avoiding threats like starvation was crucial for longevity.

Evolutionarily, losses pose immediate dangers, while gains offer incremental benefits, hardwiring a bias that prioritizes threat avoidance.

Key findings include:

This evidence underscores that loss aversion is not just psychological but deeply biological, rooted in our need for self-preservation.

While loss aversion is widely accepted, it faces critiques that encourage a nuanced view.

Researchers like Gal and Rucker argue that strong loss aversion may be overstated, with effects often confounded by status quo bias.

In some experiments, when action and inaction are separated, the bias diminishes, suggesting context matters greatly.

Critiques highlight:

Embracing these criticisms helps us avoid overgeneralization and apply loss aversion insights more judiciously in real-world scenarios.

Recognizing loss aversion allows us to harness it for better outcomes in various domains.

From marketing to personal finance, framing strategies can mitigate negative impacts or leverage the bias positively.

For example, sales tactics often emphasize avoiding loss, such as "Don't miss out on this deal," to drive action.

In investing, reframing decisions as opportunities to prevent loss rather than chase gains can lead to more rational choices.

To illustrate, here is a table of key applications across different fields:

Practical steps to overcome loss aversion include:

By integrating these strategies, we can make more informed and balanced choices that align with our long-term objectives.

Loss aversion is a powerful force shaping human behavior, with roots in evolution and evidence in neuroscience.

While it can lead to cautious or suboptimal decisions, awareness offers a path to empowerment.

By understanding that losses feel worse than gains, we can pause and question our instincts in moments of choice.

This knowledge enables us to navigate finances, relationships, and personal growth with greater clarity and courage.

Ultimately, embracing this cognitive bias not only helps avoid pitfalls but also unlocks opportunities for richer, more fulfilling lives.

References